Film review: Hillbilly Elegy

Tuesday, 23 July 2024

| Darren Mitchell

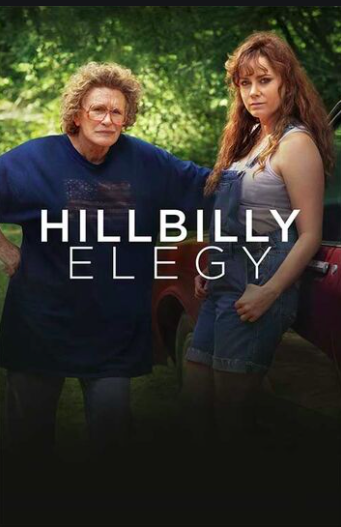

Hillbilly Elegy

A film directed by Ron Howard

Based on J. D. Vance’s 2016 memoir of his upbringing in the Appalachian region of the United States, Hillbilly Elegy opens with a preacher’s words in voiceover, the camera roving along streets of luscious green landscape with residents lazing on verandas. This idyllic setting telescopes to a large family gathering now reaching the end of annual vacation in Jackson, Kentucky. It is 1997 and Vance is an early teens member of this family sweeping up luggage, people and memories as they prepare for the car trip home to Middletown, Ohio.

One last round-up before departure produces the extended family’s ritual posed photo upon the veranda verge, the snapshot freezing the screen and heralding a cascade of earlier clan photos deftly situating the Vances as pioneering Kentucky hillbillies. What follows is Vance’s recollection of his childhood days focussed on traumatic moments, interwoven seamlessly with forty-eight hours in 2011 when ‘JD’, now a law student at Yale, takes interviews for a summer intern position, a critical path to his survival and to his success, away from Middletown. Over the course of these two days, JD is inextricably drawn back to Ohio not only in memory, but to deal with another in a never-ending cycle of crises in his mother’s life.

JD grew up in the care of his grandmother, Mamaw, his mother Bev having failed too many times in meeting the needs of a son, and elder daughter Lindsay, for a stable home and unconditional love. Mamaw offers him a room of his own away from kitchen table histrionics and family room rages fuelled by Bev’s addictions to drugs and to men. Mamaw wants for JD what she, and Bev, could not obtain, spurring him to rise above the limitations of endemic poverty, class discrimination, cultural stereotyping and family failings to reach Yale Law School, working three jobs to supplement a scholarship.

Vance’s book, subtitled A Memoir of a Family and a Culture in Crisis, hit the zeitgeist when published in 2016, extolled as bringing enlightenment to ignorant East and West coast elites who no longer understood white working-class America, especially those nestled in rust-bucket Midwest states like Ohio. In an election year that delivered the White House to Donald Trump, critics hailed ‘the most important recent book about America’ (The Economist), ‘a civilised reference guide for an uncivilised election’ (New York Times). Many concluded that Vance provided an explanation for how Trump won over the poor and unemployed, resentful victims of decades of growing inequality. Veteran film director Ron Howard’s filming of the memoir arrives at its own state-of-the-nation moment when, as another US election approached in 2020, the commentariat’s 2016 assessment of recent political and economic history can be re-examined revealing that what Vance relates is, in fact, a deeper concern for democracy itself.

With films such as Apollo 13, Frost/Nixon and A Beautiful Mind in his oeuvre, Howard is a confident cinematic storyteller. Hillbilly Elegy’s two time periods are effortlessly interwoven. The singular performances of Glenn Close (Mamaw) and Amy Adams (Bev), both of whom make frank and fearless use of their considerable close-ups, compel our acknowledgement of characters too easily stereotyped. Close’s craft is meticulous. The end-credit sequence displays home footage of the Vance family showing the uncanny resemblance between Mamaw and Close, heavily transformed by make-up and hair, as well as in mannerisms. With some prosthetic help Adams too resembles Bev physically, but there is great subtlety in her portrayal. She conjures our sympathies, offering glimpses of genuine pleading amid ample hot-blooded wailing. Through Adams’ performance JD’s conflicted feelings towards his mother are made palpable. In an early symbol of physical and emotional alignment, revisited late in the film, the camera lingers on Bev, laying ashamed on a bed with hand outstretched behind her. Unable at first to look her son in the eye, the gesture is always accepted by JD no matter how reluctant he might feel.

Vance evokes the American Dream, the hope of upward mobility, of something better. But the American Dream needs its foundation, a galvanising compass. As University of London professor Sarah Churchwell explains in Behold, America: The History of America First and the American Dream (2018), the term originally evoked the republic’s founding ideals of prosperity for all. Dreams of economic success and upward social mobility were undergirded by a shared commitment to American democracy: common values, including the institutional fabric to support opportunity and equality.

What Vance charts is a decline in moral fibre, in character, among Appalachians, crumpling in the face of joblessness and despair. His memories of his Appalachian childhood ensure we know the pains of unemployment and poverty, of real people experiencing the band-aids being ripped asunder, their dreams ravaged by austerity’s institutional decay. There is unforgiven violence in Mamaw and Papaw’s relationship, the silent domestic infection lurking behind the short-lived boom of the post-Second World War decades. There is also a destructive virus at the heart of seventies child, Bev, whose time is one of a generational precarity borne of economic decline and deep insecurity, assuaged by resort to drugs and violence.

This is what Howard foregrounds from Vance’s memoir: not the economic message alone, but the message about democracy, our contemporary institutional failure, political disillusionment and the fracturing of America. Unfettered neo-liberalism breeds uninhibited violence. Four years of Trumpism have brought new clarity to these dangers. The American Dream is not only out of reach for many individuals but in peril of losing its moral foundations, writ large in January 2021’s rampaging assault on the Capitol.

In a key scene, Howard illustrates JD rejecting this inheritance of resentment. Seeking to defend his mother’s honour, he first explodes but then ultimately resists fisticuffs as the answer. A Mamaw aphorism, ‘Where we come from is who we are, but we choose everyday who we become’, is adopted by JD as he grabs hold of his American Dream. Vance’s memoir, in Howard’s subversive interpretation, is a timely elegy for American democracy.

Darren Mitchell recently completed his PhD on Anzac commemoration rituals. He is a member of St Barnabas Broadway and Zadok film reviewer.

This review as first published in Zadok Perspectives and Papers 150: Financial Follies (Autumn 2021), 28-29. Republished with permission of the author.