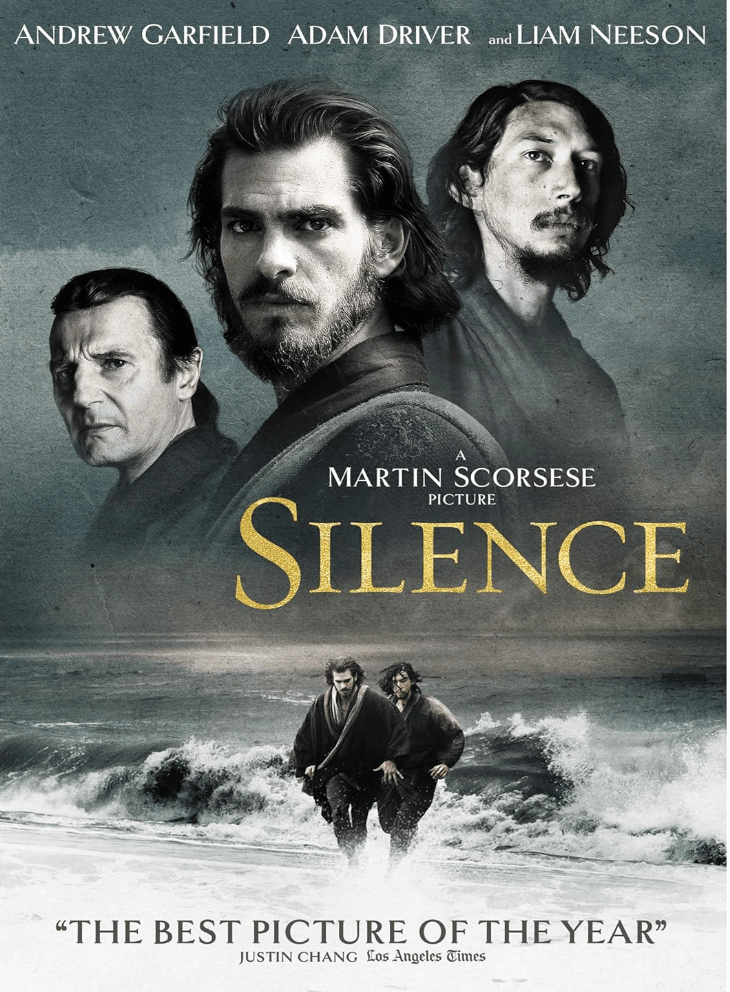

Fatalism, Faith and Sacrifice: An Analysis Of ‘Silence’

Friday, 25 October 2024

| Daniel Li

As far as passion projects go, Silence (2016) had been in the works since at least 1990 after Director Martin Scorsese read the novel by the same name in 1989. The book and film seek to capture the essential fatalism of 17th Century Feudal Japan in its hunt for Christians, Japanese and Portuguese. So why would Scorsese, coming off the back of acting as Van Gogh in the Kurosawa film Dreams, keep the production of this film in the back of his mind for the better part of 26 years? In a 2015 interview at Cannes Film Festival, he claims the book’s relevance, verve and tragedy only increased with age:

“Questions, answers, loss of the answer again, and more questions” he says. “As you get older, there’s got to be more…”

So what is the ‘more’ that Scorsese refers to?

In the same interview, he presents a striking juxtaposition between ‘the very nature of Secularism’ and whether it is right to erase that ‘which is spiritual and transcends’. That is a fundamental attraction of Silence. It asks the question: How can faith retain its relevance in an increasingly secular world? In documenting the trials of Sebastiao Rodrigues and Francisco Garupe in investigating claims of apostasy by missing Priest Cristovao Ferreira, the film moves through the stages of fatalism, sacrifice and faith to convincingly argue for an idea most intuitively possess: that spirituality and the pursuit for God is not only natural, but actually good.

When the sun shines in this film, it is rarely a positive foreshadowing. Trapped in a shack, light taunts the priests, tempting them to go outside.

‘Let’s risk it, Garupe’, Rodrigues says.

They are immediately spotted by villagers where it is impossible to tell friend from foe. In the halfway mark of the film, a shambling Rodrigues collapses by a sunlit stream, met by hallucinations of the Veil of Veronica, an image of Christ painted by El Greco. The recurring imagery frames Rodrigues as saviour – a role too weighty to fulfil. And similar to the betrayed Christ, he is met by the forces of the Inquisitor who, in an intentional allusion to Judas’ silver coins, casts money to the Christian traitor Kichjiro. Scorsese continually interchanges between physical, psychological and spiritual pain. The lack of trust that exists within the film is exacerbated by the character, Kichijiro. He is an unprincipled man, one that by his own admission is ‘weak’ – a betrayer who is forgiven by Rodrigues time and time again. Even the villagers are suspicious of other villagers, with village leader Mokichi claiming, ‘I do not know the people of Goto’. This spiritual and psychological tension collides with the real consequences of Christian conversion – death, torture and separation. In the brightest scene of the film, Scorsese shoots Father Garupe swimming at haste to save bound and drowning villagers. In a bout of exhaustion, he is drowned himself. Scorsese has accurately and piercingly replicated the dire fatalism of isolationist Japan. It is a world where a lukewarm Christian cannot exist. At times, it feels like the violence of the landscape itself opposes the Christian – swooping wide shots of mountain and sea enveloping the poor and destitute priests. This is the soil for the nourishment of great faith, it is argued. As Tertullian said, ‘the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church’.

The sacrifice given by all in Silence is total. As Mokichi is tied to a cross, he is brutalised by the white sea of Japan, wave upon wave forming a crust of salt upon skin. In the moments before death, Scorsese makes the directorial choice for Mokichi to sing a hymn – a display that a life of faith and sacrifice was not in vain. Great suffering is met by great faith. All is sacrificed. It is almost as if Scorsese made a play on the story of the rich young man who, upon Jesus asking him to ‘sell all [he has]’ and then to ‘follow me’, replied without hesitation, ‘gladly’.

What is the root of faith according to this film?

It is belief. The film frames belief through iconography – rosary beads, paper drawings of Christ and the most central motif: a hand-carved cross that Rodrigues conceals and carries until he dies. Scorsese fills his characters with a deep spirituality, one that crosses beyond verbal assent and into Being itself. In other words, there is no difference between what a Christian says and who he is. The villagers reference ‘Paradiso’ – the life thereafter – one of the ways suffering can be endured being the promise of heaven, an eternal perspective.

But the greatest display of faith is through Kichjiro. As he receives confession, he claims the ‘fires do not shine so bright’ – the fires of the burning flesh of his betrayed family. Scorsese uses Kichijiro as a representation of all Christians – ultimately weak. Kichjiro is not a hero. He feels fear, running away frequently, ‘apostatising’ by stepping on the ‘fumi-e’ – a tablet displaying the image of Christ. But he returns to Rodrigues for confession, genuinely repentant. This is the essence of Scorsese’s contention: that Christ died for the imperfect. We are frail, fallen beings in a harsh and unforgiving world, and thus, Christ’s sacrifice is necessary and generous. Scorsese has perfectly matched the balance between Christian suffering and faith.

Coming in at nearly 3 hours, Silence is a test of patience. This is perhaps the primary criticism that some have levelled – the pacing. Much of the film is consumed in dialogue. The dialogue can be obscure at times, asking the viewer to adopt its own unique lexicon: ‘Inquisitor’, ‘Padre’, ‘Apostasy’, ‘Sacrament’ and so on. I also believe there are only two moments where a character runs at speed – Garupe trying to save the drowning villagers and Kichjiro escaping from prison. The slowness of Silence is probably the reason the film was a flop at the box office, barely able to scrape 23 million dollars for its 55-million-dollar budget. But in its defence, the pace of the film is necessitated by the subject material. This is not an Avengers movie, and it doesn’t pretend to be more than it authentically is: a sincere, involved screenplay about the persecution of Christians in Feudal Japan. Imagine what this would actually be like: for the most part, a waiting and hiding game. Tense, indeed, but across spans of years. Christians locked in the confines of their impoverished villages or the confines of prison, for decades – praying, seeking, hoping and maintaining belief.

Modern Christianity in the West is a world away from the persecuted reality Scorsese has built. It is a world where it is entirely possible to profess to be ‘Christian’ but make no sacrifices, and to live reasonably comfortably. Silence is a reminder that Jesus said that ‘because you are lukewarm – neither hot nor cold – I will spit you out of my mouth’. But it is a greater analogy for Grace – the undeserved love of God for the weak. As Rodrigues is about to step on the ‘fumi-e’ – the image of Christ – God speaks to him: ‘It’s alright, step on me. I understand your pain.’

I give Silence 5/5.

Daniel Li is a Victorian Institute of Technology registered English teacher based in Melbourne, Victoria. He won the 2012 Christian Teen Writer’s Award with his manuscript, ‘A Short Walk’, and the 2020 Young Australian Christian Writer Award with his manuscript, Being Mulaney.