Constructing a theology of creativity: Pentecost shows a new Way

Sunday, 26 May 2024

| Danielle Terceiro

You can download a PDF of this article here.

Introduction

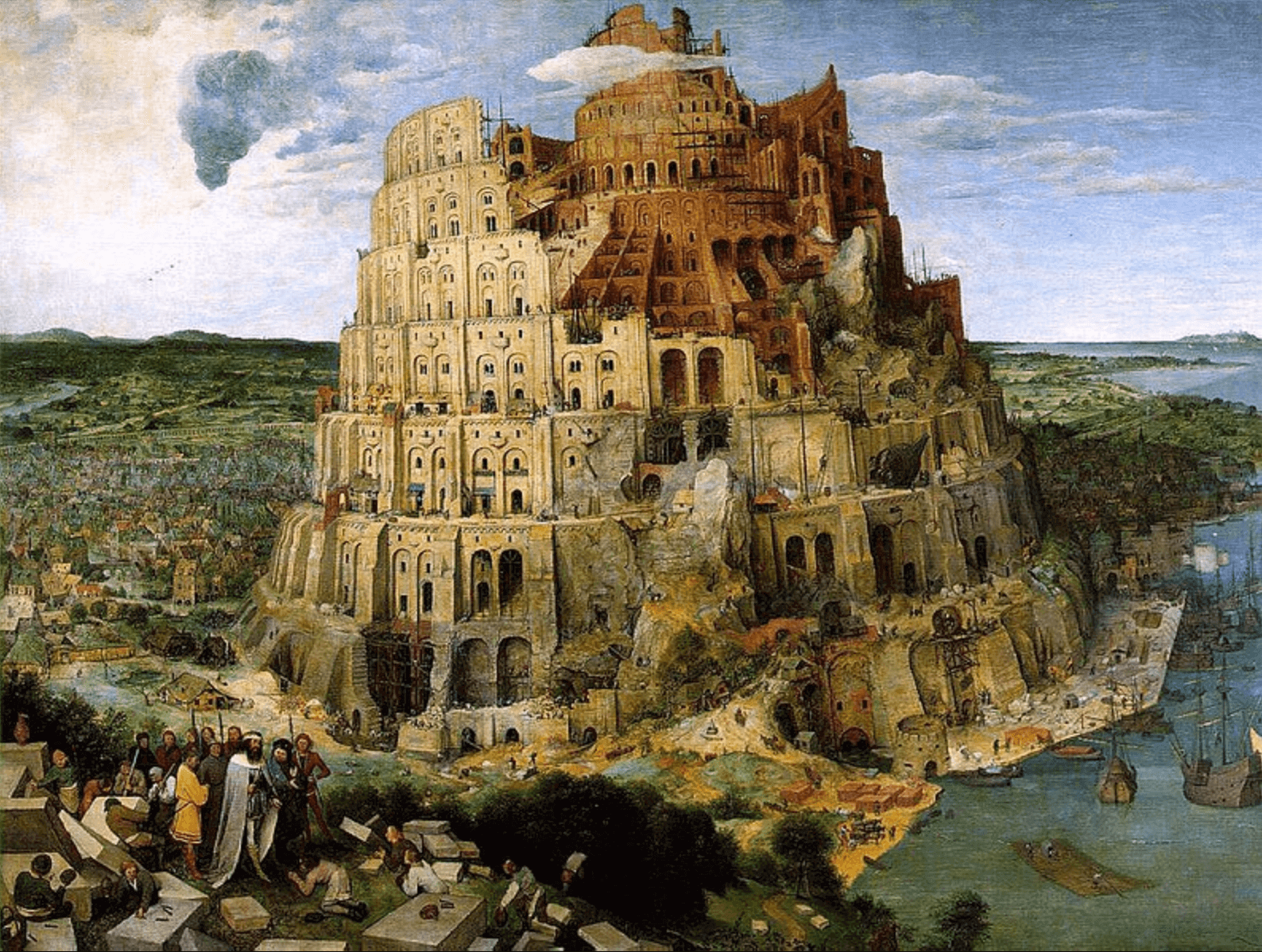

This article seeks to construct a theology of creativity. Our culture is fascinated with the idea of creativity, and this interest has ancient hyperlinks. The biblical story tells us that human civilisation began with a monumental attempt by humans to be creative on their own terms: the Tower of Babel. The biblical story leads us to the outpouring of God’s creative Spirit on Jesus’ followers at Pentecost. A Christian theology of creativity recognises that the followers of Jesus’ Way are embarked on a divinely-led journey that requires continuous improvisation and the construction of creative and diverse communities on the go.

What is creativity?

What is human creativity, and can it be observed and measured? For the last seventy years or so psychologists have become increasingly convinced that an individual’s ‘creativity’ can be measured using psychometric tests.[1] Creativity is defined with respect to what a creative person produces: work that is both novel (that is, original and unexpected) and appropriate (that is, useful and adaptive, given task constraints).[2]

Anthropologists Tim Ingold and Elizabeth Hallam[3] argue that our contemporary understanding of creativity is flawed. Our culture judges the creativity of an individual mind by the quality of that person’s output. This definition of creativity requires us to look backwards from a finished product. It assumes that creativity resides within an individual mind, sealed off from culture and history. At the same time our definition assumes that history and culture will judge the value of this output and provide the means to disseminate it so we all can become familiar with it. The problem with our working definition of creativity is that it makes it an ahistorical product of an enclosed and interior mind.

Instead, Ingold and Hallam consider creativity to be a forward-looking, improvisational process, and intensely relational. Improvisation is relational ‘because it goes on along “ways of life” that are as entangled and mutually responsive as are the paths of pedestrians on the street’. And in this extended metaphor of creativity as a journey, ‘every idea is like a place you visit. You may arrive there along one or several paths, and linger for a while before moving on, perhaps to circle around and return some time later’. This understanding of creativity honors the creative, improvisational work of the builder as much as the work of the architect who creates a blueprint or design. There is always a ‘kink’ between the world and the architect’s idea of it, and builders inhabit that kink.

The improvisational conception of creativity does not oppose creativity to tradition. Rather, improvisation is an important way in which a community transmits its culture and adapts tradition to its everyday concerns. Hallam and Ingold describe this as the ‘human habit of simultaneously improvising and striving to make things stick’.[4] In the early church, for example, the singing of ‘psalms, hymns and songs from the Spirit’ (Ephesians 5:19) was both a creative improvisation and the way in which the teaching of the apostles was ‘made to stick’ in a relational context.

The Tower of Babel: Humanity’s Unfinished Product

How did humanity arrive at an idea of creativity as finished product rather than as a journey or process? The Tower of Babel story in Genesis 11 gives some clues. In the biblical narrative a group of people applies a novel idea to building: the use of brick and bitumen instead of stone (Gen 11:3). This community seeks to build a city that makes their ‘name’: a city that breaks into history with a monumental bang. Genesis 11 tells us that the city that the people are constructing is to have a tower within it. It seems that this tower will be a monument to the people’s creative genius. The pride-full ‘overreach’ of the people is like a collective version of the overreach of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.[5] This monumental overreach results in oppression: it was at Babel, and later within Egypt, that city building projects erased individuality and reduced free people to slaves.[6]

The LORD closes off clear communication between the people and as a result the people are scattered to journey through the earth. The curse on language renders it impossible for the builders at Babel to continue to engage in the ‘creative improvisation’ necessary to realise any architectural blueprint for the Tower.

Cultural theorist Susan Stewart notes that the Hebrew scriptures are very different to the ancient Mesopotamian city laments, where gods unleash destruction, humans rebuild and gods return. She notes that the Hebrew scriptures ‘are not stories of slow ruin, of long sieges and equally balanced forces in heaven and on earth: here ruin is sudden and overwhelming’.[7]

The story of the Tower of Babel ends with a sudden ruin. The Tower of Babel also begins another story: the story of the creative improvisation of peoples on the go. Ironically, creative potential opens up because of humanity’s scattering throughout the earth. Humanity is forced to improvise new communities on the go, in a manner that is a blessing as well as judgment. The failed project of the Tower of Babel prompts humans to start their creative journey for real and opens up possibilities for creativity not available in the monolithic and ‘meglo-maniacal’[8] society at Babel. Stewart notes that, even though the transparency of language was cursed at Babel, ‘yet God did not strike the builders mute: like Adam and Eve in a world that is wholly future, they must start over, beginning again to build structures of intelligibility, to work and re-form from the ground up’.[9]

The proliferation of different languages in the wake of the Babel event is itself a creative opportunity: the creativity scholar Enrica Piccardo notes that language diversity can be conducive to social transformation.[10] In order for creativity to emerge and for change to occur, a ‘plurilingual competence’[11] must be fostered. A community with plurilingual competence is characterised by more than one language or dialect in interactions between people, by forms of code-switching and code-mixing.[12] Plurilingualism can challenge a ‘dominant monolingual’ vision, helping to understand that language is not simply putting a ‘label’ on objects but facilitates new meaning by putting culturally dissimilar concepts and terms side by side.[13] Piccardo considers that the emergence of creativity within a plurilingual society requires nurturing in education and interactions over time.[14] It also requires a willingness to live ‘at or near the edge of chaos’ within a system.[15]

Those at Babel downed tools and left, rather than living at or near the edge of chaos. They started afresh, forced to improvise community on the go. The Tower of Babel was cursed as a monumental project, but the journey away from the Tower was an opportunity for people to make up things along the way, including language. At the Pentecost event God gathers back his plurilingual peoples from the corners of the earth and blesses them.

Pentecost: A New Way

In the biblical account, God pours out the Holy Spirit onto the intercultural assembly gathered in Jerusalem for the Feast of Pentecost (Acts 2). The new community, following the divine Way (Acts 9:2), is made aware that its creative purpose is the creation of loving community itself, a fellowship of believers dedicated to the apostles’ teaching (Acts 2:42-47). The Pentecost event affirms the creativity of young people, and the Apostle Peter repeats the words of the Old Testament Joel, who anticipated that young people would be helping the new community with forward-looking, prophetic words (Joel 2:28 and Acts 2:17). The community in the Book of Acts demonstrated the kind of ‘making it stick’ creativity noted by Ingold and Mallam. For the author of the Book of Acts, the church is a new and dynamic entity with connections to old promises.[16]

Walter Brueggemann talks about Babel as demonstrating an inappropriate ‘self-made unity’ and a ‘fortress mentality’.[17] Pentecost and its xenolalia – people miraculously understanding foreign languages around them – is often seen as a ‘reversal’ of the curse on language at Babel. However, Pentecost is much more than a simple reversal of Babel. The ‘communal voice’ of God is present in the languages spoken and understood at Pentecost.[18] And while Christ brings about the unity of his body, the Spirit mediates and sustains a diversity. At Pentecost the singular – the individual – is preserved within the communal.[19] Pentecostal theologian Daniela C. Augustine considers that Pentecost is a reversal of the ‘consequences of Babel’s imperial project’, and that God redeems our human community and empowers it to ‘choose and embody the life of God on earth as diversity in unity sustained by love towards God and neighbour’.

The ruins of Babel are a monument to humanity’s failure to live up to this kind of community, to work out a form of interdependence and interaction that honoured and nurtured the creative individuality of those in community. Then Pentecost follows on as a gift from God to humanity, bringing the assembled group back to the edge of multilingual chaos, and then bringing them back from the brink with the gift of xenolalia. The emergence of language is normally an iterative creative process that involves multiple interactions between speakers and ‘cycles of emergence’. Pentecost is this creative process, compressed in time. What God does at Pentecost is, perhaps, to give us a glimpse of the paralanguage of worship that will develop through eternity as multitudes from every nation and tongue gather together (Revelation 7:9).

God constructs a new temple or a new body with this diverse community, and this community follows a new ‘Way’. In his book, The Charismatic City and the Public Resurgence of Religion, Nimi Wariboko notes that the concept of church as body should not be understood as a simple aggregation of individuals. This simple adding together of people is problematic as it is static and solely about ‘making and unmaking’. Instead, the church is real because it is ‘a process, a pattern of actions and movements by the body, a series of events rather than a composition of people’.[20]

And perhaps this process is the creative undoing of what was attempted at Babel: what Susan Stewart describes as the principle of ‘addition and accumulation’ as brick is put on brick.[21] Babel is a creative shortcut that we should never have taken. Pentecost shows us the better, non-linear Way. Wariboko describes the ‘quasi-random, wind-like movement of the Holy Spirit’, putting the collective body into motion along ‘spiritual-energy superhighways’ that are linked in rhizomatic networks. This dynamic movement is what Wariboko calls ‘charismatization’.

If the Tower of Babel account in Genesis 11 shows a people intent on a monolithic and stifling expression of culture, then the Pentecost event shows the creative counter to this: a charismatic community brought together in their diversity through visual, verbal and multisensory signs and wonders; a community filled by the Spirit to ‘pour out’ their lives in a creative, communal worship of the God who came down to them. At Babel, God judged the people, but it was not judgment through water or fire, as might have been expected.[22] It was through a curse on language. And Pentecost is a creative and unexpected mixing of Old Testament catastrophe. Fire and water become elemental agents of blessing. Tongues of fire separate and rest on each individual’s head. The language used to describe the coming of the Holy Spirit is ‘liquid’: it is poured out on all people. And of course, there is the water of baptism into which Peter invites believers (2:38). Pentecost as a multi-sensory event is a creative reminder of the creative speech-act of Yahweh at Sinai[23], where Yahweh’s words came amid thunder, lightning, trumpet and smoke (Exodus 20:18).

Rowan Williams describes the essence of creativity as kenotic, a pouring out of the self for the other. According to Williams, creativity is the ‘search for a justice that is beautiful, a justice that uncovers what the world fundamentally is: a world of interdependence and interaction, a world in which self-forgetting brings joy, common, shared joy’.[24] He writes of how God’s people have a creativity, and not just as a mirror aspect of the creative Creator God, but as a participation in the self-emptying, kenotic love of the Trinity. Williams notes that ‘The God who creates a world of freedom, a world that is itself, is a kenotic God, a self-giving, a self-emptying God whose being is for the other. And as we understand this in the eternal life of the Father, the Son, and the Spirit, we understand how it is in creation’. Human creativity should be linked to a ‘holy wisdom’ and a ‘self-forgetting’, ‘the denial of the selfish will in the artist’s work, the denial of a crude individualism in the social realm’.

There is a humility built into this creative way of life. Humans need to know that they can never speak a world of beauty into existence or triumph over chaos and convert it into order. However, while the creativity that humans are invited into may not have the ‘wow factor’ of God’s chaos-ordering creation of the world, it is, as theologian Barbara A. Holmes notes, ‘an ordinary practice, a practice both individual and communal, that is imbued with God’s presence and grace’.[25] The practice of everyday creativity within community can be a constructive and beautiful response to the world that God has already spoken into existence, that is, to big-Creator creativity.

Pentecost is God’s creativity at joyful play in community. The Holy Spirit equips the church, Jesus’ body on earth, to change the world. Not through monumental innovation but through self-giving love that adapts itself to the other. A Christian theology of creativity can help critique our culture’s intense individualism and drive for output. A Christian theology of creativity does not backwards-engineer itself through a focus on the monumental past, but rather takes joy in the improvisation of a future-oriented community that is on the Way, together.

Danielle Terceiro is a PhD Candidate at Alphacrucis University College, Sydney.

Image credits

Lucas Franchoys, The Descent of the Holy Spirit in Sint-Janskerk, Mechelen, Belgium. On sidepanels: the preaching of Peter and Paul. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Pieter Brueghel, The Tower of Babel. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Since Guilford gave a presentation to the American Psychological Association in 1950, proposing that creativity could be studied in everyday subjects using paper-and-pencil tasks. See Robert J. Sternberg and Todd I. Lubart, ‘The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms’, in Handbook of Creativity (Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 3–15.

[2] Sternberg and Lubart, ‘The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms’.

[3] Elizabeth Hallam and Tim Ingold, ‘Creativity and Cultural Improvisation: An Introduction’, in Creativity and Cultural Improvisation, eds Elizabeth Hallam and Tim Ingold (Oxfordshire, UK: Taylor and Francis, 2021).

[4] Hallam and Ingold, ‘Improvisation and the Art of Making Things Stick’, in Creativity and Cultural Improvisation.

[5] Claud Westermann, Genesis: Text and Interpretation (Grand Rapids, MI: WIlliam B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1987).

[6] Judy Klitzner, Subversive Sequels in the Bible (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2009), 54.

[7] Susan Stewart, The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2022).

[8] Miroslav Volf, After Our Likeness: The Church as the Image of the Trinity (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1998).

[9] Stewart, The Ruins Lesson.

[10] Enrica Piccardo, ‘Plurilingualism as a Catalyst for Creativity in Superdiverse Societies: A Systemic Analysis’, Frontiers in Psychology 8 (2017), 1–13.

[11] Piccardo, ‘Plurilingualism as a Catalyst for Creativity, 5.

[12] Piccardo, ‘Plurilingualism as a Catalyst for Creativity, 5.

[13] Piccardo, ‘Plurilingualism as a Catalyst for Creativity, 8.

[14] Piccardo, ‘Plurilingualism as a Catalyst for Creativity, 11.

[15] Piccardo, ‘Plurilingualism as a Catalyst for Creativity, 9-10.

[16] Darrell L. Block, A Theology of Luke and Acts: Biblical Theology of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012).

[17] Walter Brueggemann, Genesis (Louisville, KY: Presbyterian Publishing Corporation, 2010).

[18] Daniela Augustine, Pentecost, Hospitality, and Transfiguration: Toward a Spirit-Inspired Vision of Social Transformation (Cleveland, TN: CPT Press, 2012), 29.

[19] Augustine, Pentecost, Hospitality, and Transfiguration, 29.

[20] Nimi Wariboko. The Charismatic City and the Public Resurgence of Religion (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2014). Chapter 9.

[21] Stewart, The Ruins Lesson.

[22] Stewart, The Ruins Lesson.

[23] Augustine, Pentecost, Hospitality, and Transfiguration, 32.

[24] Rowan Williams, ‘Creation, Creativity and Creatureliness: The Wisdom of Finite Existence’, in Being-in-Creation: Human Responsibility in an Endangered World (New York: Fordham University Press, 2015).

[25] Barbara A. Holmes, Dreaming (Indianapolis: Fortress Press, 2012), 44.